| dior13dior13 2014/9/3 00:21 |

佛教新聞天地2014/07/17 01:47

英國廣播公司(BBC)紀錄片揭發,西班牙在佛朗哥統治期間,全國醫生、護士,以及天主教神父和修女狼狽為奸,組成龐大嬰兒販賣網絡,50年間偷走共30 萬名嬰兒,轉售予領養者圖利。惡行令無數受害家庭跟親生骨肉分離,被販賣兒童今天長大成人,紛紛要求政府正式調查,但與親生父母團圓的機會十分渺茫。

《每日郵報》報導,佛朗哥於1939年掌權,他向對其政權有威脅的家庭落手,偷走他們的嬰兒。但他於1975年去世後,在全國擁有極大影響力的天主教會仍 繼續販賣活動,操控醫生護士從事惡行。西班牙要到1987年才從醫院手中規管嬰孩領養,販賣活動維持長達50年。專家相信,從1960年至1989年期 間,有15%的領養案件屬於非法買賣。BBC紀錄片《世界:西班牙被盜嬰兒》(This World: Spain's Stolen Babies)詳細記錄事件。

謊稱夭折 偽造出生證明

受害人不少是未婚懷孕少女,醫院會向她們謊稱嬰兒夭折,並阻止她們看嬰孩「遺體」和「埋葬」過程。醫院其後把嬰兒賣給無子女的夫婦。多數領養者對實情毫不知情,以為領養的嬰兒都是遭人拋棄。醫院再偽造嬰兒的出生證明書,寫上養父母的名字。

事件沉寂多年,最終由當年被領養的莫雷諾及巴羅索揭發。莫雷諾「父親」臨死時承認,當年跟巴羅索父母一同用巨款向神父買下兩人。巴羅索指金額可比房子價格,他父母分期付款,用了10年才能還清。事件曝光後,引起全國哄動

Searching for Spain’s stolen babies

An estimated 300,000 children were taken from their mothers at birth and placed with adoptive families. The trouble is, most don’t know it.

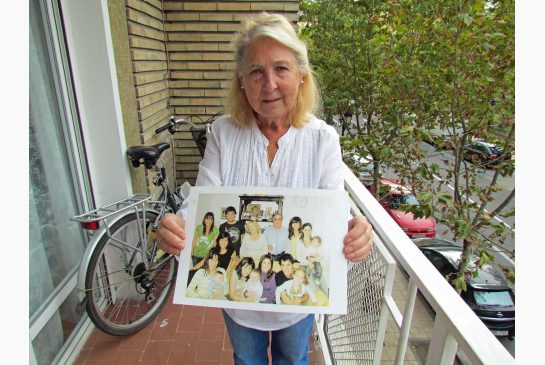

MARY VALLIS / TORONTO STAR Order this photo

MARY VALLIS / TORONTO STAR Order this photo At 70, Luisa Fernanda Marin Valenzuela is surrounded by a bustling family of nine children and seven grandchildren, but she believes there is someone missing from her family portrait. Valenzuela says a tenth child, a tiny son, was stolen from her after she gave birth in 1974, although she was told the child had died. "The uncertainty of not really knowing...that really is shattering," she says.

By: Mary Vallis Toronto Star, Published on Tue Nov 08 2011

ZARAGOZA, SPAIN—In November 1974, Luisa Fernanda Marin Valenzuela stood in a doorway at a medical clinic. A male nurse held one arm and a nun held the other. About 36 hours earlier, she had given birth to a baby boy. Far across the room, she could see a tiny baby’s naked body on a table. They told her it was her dead son.

She wanted to get closer, to hold him, to cover his cold skin, perhaps even whisper his chosen name, Antonio. But the nun and nurse refused to let Luisa, who was wracked with grief, move closer to the child. Instead, they led her away.

“She’s going to faint, she’s going to faint,” she remembers them saying as they pulled her back. “Take her home.”

It was the first and only time Luisa saw the baby they said was her son. Thirty-seven years later, she is convinced it wasn’t him. She, like hundreds of other mothers across Spain, believes her child was stolen.

What began as a trickle of revelation about General Francisco Franco’s ideological cleansing by taking children from their parents is now a fully engaged scandal in a country wracked by debt, unemployment and civil unrest. As many as 300,000 babies, Spaniards have been told, were wrested from their mothers between 1960 and 1989 by a network of doctors, midwives, priests and nuns who then sold them to infertile couples for huge sums.

The scandal emerged four years ago, when a dying father revealed to his son, Juan Luis Moreno, that he and a childhood friend, Antonio Barroso, had, in fact, been bought from a priest and a nun for about 200,000 pesetas each in 1969, money that could have bought a small flat. Pesetas were the Spanish currency until 2002.

Nobody knows for sure how many children — and parents — are living false lives. Nearly 1,000 lawsuits have been filed in courts ill-prepared to handle them. And with the scandal has come a stream of shocking details — tiny corpses kept in freezers as decoys to show grieving parents; nuns with million-dollar real estate holdings and caskets exhumed after decades found empty.

Plunged into uncertainty, questioning mothers and children are paying hundreds of euros for their own DNA testing; the results are ripping their families apart.

So far, six stolen children have been reunited with their biological families, providing many with hope that their long lost children are alive. It is only now that many have even considered the prospect that they may have been told something other than the truth, including Luisa.

She is 70 now, a mother of nine and grandmother of seven. Remembering those moments long ago, she wipes tears from her eyes again and again.

“You can overcome death. It takes a long time, it’s very painful, but you can overcome it,” she says. “But the uncertainty of not really knowing . . . that really is shattering.”

The stories of the many grieving mothers bear striking similarities. Many were anesthetized during labour. When they awoke, they were told their babies had died. Many never held their babies, or even saw them.

Stolen babies have a long history in Spain. During the reign of General Francisco Franco (1936-1975) tens of thousands of children were stolen, beginning in the 1930s. Children were taken from left-leaning parents and placed with more politically suitable families to protect their “moral education.” Others were taken from single mothers and given to “proper” Catholic homes.

“In Spain, the precedent was really set during the civil war,” said Antonio Lafarga Sábado, Luisa’s husband. “But the weird thing is, it just carried on. It didn’t stop.”

As Spain became a democracy, those with access to newborns appear to have carried on the tradition because the trade was so lucrative.

The story of Moreno and Barroso, who grew up in Vilanova i la Geltrú, a seaside town about 50 kilometres south of Barcelona, started the avalanche of current courts cases. After the elder Moreno’s deathbed confession in 2007, so much made sense. Moreno understood why he towered over his diminutive father and looked nothing like his mother.

The childhood taunts Barroso endured in the schoolyard — children claiming he wasn’t really his mother’s child — came rushing back. She’d always insisted their claims weren’t true, and even told him vivid stories about her labour pains.

When Barroso was in his teens, he went to a local registry office and pulled a copy of his birth certificate, which listed the name of his adoptive mother; the staff insisted there could be no mistake. He put it out of his mind until the confession came; by that time he was 38.

“I’d always suspected it,” Barroso, 42, says, fiddling with a copy of his inaccurate birth certificate. “When I was young, there was no real way to confirm it, but now, with DNA tests available, the whole thing becomes so much clearer that all my life has been a lie.

“I’ve been lied to and I’ve been fooled.”

The men took DNA tests that confirmed the dying man’s story. Barroso has since abandoned his career in commercial real estate. He has filed lawsuits at every level in the Spanish court system and founded the National Association for Victims of Irregular Adoptions (Anadir).

More than 1,800 people are members of the group, which maintains a DNA database for parents who fear their babies were stolen, and people who suspect they were trafficked.

About 930 lawsuits have been filed. The majority have been rejected; judges cite statutes of limitations, a lack of evidence and the fact that key witnesses are dead.

Spain’s laws have also made investigation difficult. Babies that die within 24 hours are considered aborted fetuses and are often buried together in their own section of cemeteries — making it hard to extract DNA evidence, according to Lorenza Álvarez, who is coordinating the stolen baby cases for Spain’s attorney general’s office.

Still, a small but growing number of cases are proceeding. Tiny graves are being exhumed throughout Spain. Some are empty; others contain only wads of medical gauze or bandages, not tiny bones.

In two caskets, investigators found remains that have no genetic link to their supposed parents — evidence, Barroso reasons, that the babies were swapped with those of couples who had stillborns.

One woman has told reporters that in 1969, a priest encouraged her to fake a pregnancy until a child became available for purchase. And a man who drove babies’ caskets to a cemetery in southern Spain says at least 20 of the boxes were far too light to hold children’s remains — or, for that matter, to hold anything at all.

Spanish journalists who investigated a clinic in Madrid that is listed in many legal claims found a baby’s corpse in its freezer. There have been suggestions it was kept there to show parents who demanded proof their children had died.

The scope is staggering. Barroso feels he is single-handedly leading the charge for justice. He is tired; dark circles hang beneath his eyes as he explains his frustration.

“It’s shameful that Spain, which likes to presume to be a law-abiding society, one that wants to give the impression of being a democratic, modern society, should have had this going on,” Barroso said. “You basically have to laugh so as not to break out crying.”

When Barroso learned he had been bought, his mother was ill. He surreptitiously swabbed her cheek for DNA tests that proved she was not his biological parent. She eventually confessed that a nun she had befriended did her a favour.

He and Moreno followed the trail to another nun, now 85, and in hospital. The men have visited her several times — hoping she will reveal the names of their real mothers. But she has revealed nothing.

“She remained absolutely unmoved,” Moreno says. “She said her conscience was at peace. She helped mothers in a disgraceful situation. She had nothing but peaceful thoughts.”

The nun has not been charged with any crime. The Roman Catholic Church has not commented.

Barroso and Moreno have learned that she owns seven properties, estimating her worth at one million euros (nearly $1.4 million Canadian). One of the properties was inherited and another was donated, but the remaining five appear to be outright purchases.

“How is it possible that a nun with espoused vows of chastity, poverty and obedience should be worth so much money? How has she accrued so much property?” Moreno asks.

Moreno and Barroso have presented their lawsuits at all levels in the Spanish court system, but they have been consistently rejected.

In January, Anadir presented 261 cases to Spain’s attorney general and held a rally in an attempt to draw public attention. It was then that the government took the issue seriously and began referring cases to provincial judges.

The prosecutor’s office has since authorized exhumations and some cases are proceeding, Álvarez said.

Luisa’s case is not among them. Her lawsuit was dismissed in late September because the midwife and doctor are both dead.

Sitting in her living room, surrounded by family photographs, she fingers a photocopy of the burial record from the cemetery that contains her family niche.

At the clinic, she was told her newborn had died around 11 a.m. on Nov. 24, 1974, about 36 hours after his birth. She says she refused to leave the clinic until she saw his body.

But the burial record shows that by the time staff showed her the baby’s body, he would have already been buried.

What’s more, her husband Antonio clearly remembers picking up his son’s remains and taking them to the cemetery the following day, on Nov. 25. But that date does not appear in any of the records.

The couple, who were then in their 30s, trusted their doctor and the clinic. They had already delivered two healthy girls with his help.

“All my children have been born perfectly healthy,” Luisa says.

“The likelihood here was that this boy was going to be a very healthy little boy. That’s why I think it happened to us.”

She returned to the same doctor for four more births. Strangely, he waived his fees for one birth. Did he feel guilty, they wonder.

Their flat is always bustling with activity. Down the hall, some of their daughters and grandchildren have gathered for a family lunch.

One of their granddaughters scampers down the hall for a kiss on her way to school. Luisa gives her a tight hug.

“Other people say, ‘Listen, you’ve got nine and they’re all extremely healthy,’” Luisa says. “But there’s one that’s missing.”

“There is one missing,” echoes her husband.

| dior13dior13 2014/9/3 00:22 |

On the trail of Spain's stolen children

More evidence is emerging of a clandestine network that organized illegal adoptions

"You cost the same as a herd of pigs" http://elpais.com/elpais/2011/03/07/inenglish/1299478844_850210.html#despiece1

JESÚS DUVA / NATALIA JUNQUERA 7 MAR 2011 - 16:15 CET

Recomendar en Facebook 24

Twittear 2

Enviar a LinkedIn 0

Enviar a Tuenti Enviar a Menéame Enviar a Eskup

Enviar Imprimir Guardar

In the decade following the end of the Spanish Civil War, an unholy alliance of doctors, priests, and General Francisco Franco's secret police systematically took thousands of children from vulnerable women known to have supported the Republican cause. These women were often in prison, or their husbands had been killed or were also in jail. It was seen at the time as an effective way of inflicting a lasting punishment on those who had backed the wrong side in the war, at the same time as preventing the appearance of a new generation of "reds" by placing the children in the care of families who supported the new regime.

But over recent years, it has emerged that the practice continued beyond the war, which came to an end in 1939, and was widespread throughout the Franco era - even after the dictator died in 1975. A network of Catholic Church-run children's homes and private hospitals would take newborn infants, typically from young, impoverished single mothers, who were told that their baby had died. Estimates put the total number of children who may have been illegally adopted between 1950 and 1980 at around 300,000.

Around 300,000 children may have been illegally adopted from 1950 to 1980

The Franco regime stole from families that might pass on the "red gene"

People who took part in the trafficking could be charged with abduction

The network has been described as "a good mafia" by one of its own members

más información

• Prosecutors hear witnesses in stolen baby cases

http://elpais.com/elpais/2011/03/11/inenglish/1299824448_850210.html

• Ex-nun condemns baby trafficking

http://elpais.com/elpais/2011/03/29/inenglish/1301376043_850210.html

"There was great demand for children to adopt, and there were a lot of people prepared to create the means to meet that demand," says sociologist Francisco González de Tena, who has spent several years researching the subject. As is revealed by the growing numbers of adoptees and mothers who suspect that their babies didn't die at birth, but were taken from them, it has become clear that this is a problem on a nationwide scale, affecting thousands of people.

It was Antonio Vallejo-Nájera, a psychologist at the service of the Franco regime and the formulator of pseudo-scientific theories regarding race similar to those of the Nazis, who came up with the idea of "positive eugenics" aimed at "multiplying the select and allowing the weak to perish." Fortunately, as far as is known, the Franco regime never set up its own equivalent of Hitler's Lebensborn - a supposedly master race produced from selective breeding - but it did steal children from women or families that might pass on the "red gene."

"I heard heart-breaking cries. 'Don't take her away from me! I want to take her with me to the other world!' Another shouted out, 'I don't want to leave my child with these murderers. Kill her with me...' A terrible struggle was underway: the guards were trying to rip babies from the arms of their mothers, who defended themselves to their last breath. I never imagined that I would ever witness such a terrible scene in a civilized country." The words of Gumersindo de Estella, the chaplain of the Torrero prison in Zaragoza, testify to the theft of dozens of children from female Republican prisoners, who were subsequently shot. In 1941, the authorities were allowed by law to change the names of children taken from executed prisoners, effectively making it nigh impossible for them to be traced.

María Calvo was among the lucky few to have traced a family member. She was among the more than 34,000 children evacuated to France by the Republican authorities during the Civil War. But when Franco demanded the return of the children, María Calvo was separated from her sister Florencia, and they were sent to different families. María Calvo says she was picked out of a line of other boys and girls at a children's home in Madrid, and taken to live in Murcia. Her sister was sent to an institution and remained there until she was 18.

González de Tena, who was instrumental in the 2009 decision by Judge Baltasar Garzón to order provincial judges to investigate the "disappearance" of children taken from left-wing families, estimates that by 1950, around 30,000 such children had been taken into adoption by families who supported the regime.

"After that, the next objective was to take children from single mothers, young mothers and the poor. They were still the defeated, the vulnerable, those unable to protest," says González de Tena. "They were given to the victors. Obviously, who else could afford to pay the equivalent of 1,200 euros for a child back in the 1960s?"

The link that enabled the practice of taking children from their mothers - now through deception rather than by force - up to and beyond the death of Franco, was made up of a network of priests and nuns, as well as Catholic doctors, judges and notaries, many of them belonging to the highly secretive Opus Dei movement.

"We feel like trees without roots," says María, who was put up for adoption in the San Ramón de Madrid clinic, which operated as a baby factory until 30 years ago, and was run by Dr Eduardo Vela, who, aged 77, is still practicing.

On January 27, ANADIR, an association that represents illegally adopted children, presented the Attorney General's office with a list of 261 cases of children stolen from different regions around Spain between 1950 and 1981. A month later, as the story made headlines, another 500 people came forward, saying that they suspected they too had been taken from their mothers illegally. Other associations have around 700 members.

The thefts started coming to light after Judge Baltasar Garzón tried to investigate Franco's human rights abuses in 2008. Garzón was forced to drop his inquiry, but non-political cases of illegal adoptions also began to emerge.

Attorney General Candido Conde-Pumpido, however, was expected to reject that argument. He will probably not open a nationwide investigation into 261 cases that were brought to him by Anadir, but will advise people seeking such inquiries to turn to regional courts. People who took part in the trafficking could be charged with abduction and crimes against humanity, offences that do not come under the statute of limitations.

In almost every case, the modus operandi was the same: the mother was told soon after birth that her child had died, and that seeing the deceased infant would only cause further distress.

In reality, as González de Tena notes, there was a nationwide network of priests, doctors and other officials on the lookout for vulnerable pregnant young women and families looking to adopt without having to go through the proper channels. They participated in it for economic gain, or believed that it was ethical to place children from poor backgrounds in wealthy families.

In some cases, mothers were pressured and persuaded during their pregnancy that the best thing would be for the hospital to find a home for the baby as soon as it was born. Mothers who later repented found that they were up against a wall of silence, and that the authorities were only interested in protecting the rights of the usually wealthy families that had adopted their children.

Couples looking to adopt a child in the late 1960s or 1970s would have to pay the equivalent of around 18,000 euros today. Enrique Vila, a lawyer who represents ANADIR, says that larger sums were paid, depending on the age of the child, or if the couple wanted one sex or the other.

Church-run children's homes would organize open days when prospective parents could pick out a particular child after examining them closely. Until 1970, parents could register adopted children as their own, effectively eliminating any possibility of a child ever locating his or her biological mother.

Another adoption organization active at this time was AEPA, founded in 1969 by Gregorio Guijarro Contrera, a former Supreme Court attorney, and adopted father of twin girls. AEPA was backed by the equivalent at the time of the Youth Ombudsman and leading Catholic Church charity Cáritas Spain.

Guijarro told EL PAÍS in July 1979: "We are an association that sees adoption as a final solution in this society when every effort to fit a child into its own family has failed."

Asked about irregularities in the adoption process at the time, or even the existence of a hidden network that offered children to families, Guijarro said: "This is a theory that many adoptive parents themselves have contributed to, fearful of the shame associated with adopting a child. In some cases, mothers have pretended to be pregnant, and they have tried to have the child registered as theirs by birth. To do this, they are helped by people who put them in contact with a pregnant mother prepared to part with her child. They pay the costs of the birth, and then keep the child."

Adopting through official channels was a long, laborious, and costly process, and in many cases fruitless. Applicants would typically receive a letter after a couple of years telling them: "There are a great many requests, and very few children available." In 1980, the provincial government of Madrid had 6,000 applications pending, and had not carried out a single adoption process in years. But the reality was that for many years before, and for some years afterwards, thousands of children were adopted through clinics and maternity hospitals throughout Spain with the help of priests, nuns, social workers, and lawyers. The network has been described by somebody who was part of it as "a good mafia."

In 1980, Guijarro told EL PAÍS to talk to Sister María Gómez Valbuena, the head of social services at the Santa Cristina hospital in Madrid. She subsequently admitted that she handled around 1,000 adoptions a year, and was firmly against the Madrid provincial adoption office taking over the process.

"Today, with things as they are, the quickest and most efficient way by far to adopt a child is to get involved with the people who are directly involved with these kind of children: social workers, nuns, etc. If you get on with them better than everybody else on the list, it's easy," said Guijarro. He died shortly afterwards in a car accident. His successor at the head of AEPA, José María Cruz, said in 1981: "There are cases of exploitation in every country, of children being sold, of dirty business, abuses that changes to the law attempt to rectify."

It was not until 1987 that the government finally passed adoption legislation that brought procedures into line with those in other developed countries.

西班牙30萬嬰遭販賣神父修女狼狽為奸

http://blog.udn.com/acewang3005/15139212

便便陳發言論,就貼一篇天主教醜聞,直到他改變小心眼為止。

改變小心眼當個堂堂正正的君子,就改封他為變變陳。